In recent years citizens have become increasingly frustrated by a tax system which they perceive as burdensome, difficult to understand, and in many respects unfair. At the same time, growing numbers of business people have become aware that the current tax system often undermines entrepreneurship, competitiveness, and economic efficiency. Concern with taxation is not unique to Canada. Similar opinions are widely held in the United States, Britain, continental Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, and have resulted in changes, or proposals for change, which promise to reform fundamentally many of these taxation systems. Indeed, the United States, Canada's closest economic partner, is currently in the midst of a massive overhaul of its tax rules involving a broader tax base and sharply lower tax rates. This will have major implications for Canadian tax and economic policies.

The Business Council welcomes recent federal government plans for a comprehensive review of the Canadian tax system. Such a searching appraisal is badly needed, and should lead to proposals for reform that command broad support throughout the country. In order to participate constructively in the national debate on tax policy issues, the Business Council decided to establish a Task Force on Taxation Policy in 1985. The Task Force's mandate was to prepare a taxation policy framework and a set of general policy proposals for Canada . This paper represents the fulfillment of those objectives. The purpose of the policy framework is not to offer detailed recommendations on every aspect of the tax system, but instead to articulate an integrated set of principles and policy directions against which specific reform proposals can be assessed and evaluated. In addition, the paper offers a number of general policy recommendations in various areas illustrating the direction we believe the tax system must move in the years ahead if Canada is to maintain or improve its position in the increasingly competitive global economy.

We wish to make an important point at the outset concerning the linkage between tax policy and the broader subject of fiscal policy and the deficit in Canada. Changes in taxation policy can have significant impact on government finances, and thus have obvious implications for fiscal policy and government deficits at both the federal and provincial levels. The policy framework ideas and the more specific policy recommendations put forward in this paper have not been "costed" in a precise way. However, the proposals, taken together, are designed to be "revenue-neutral." In other words, they are not intended to result in a reduction or increase in the total tax receipts of governments.

There are many in Canada, including most of the business community, who believe the overall tax burden facing Canada is excessive. The Business Council shares this concern. We have a large and expensive public sector whose current costs already significantly exceed aggregate government revenues. While this issue is important it is deliberately not addressed in these proposals. Given this, the vital question becomes how to pay for government programs and services with the least damage to the fundamental elements from which a prosperous, efficient, and flexible economy can be constructed. This is the challenge which lies at the heart of both tax policy reform and this Business Council Task Force Report.

As outlined in the next three chapters, the Business Council supports a major overhaul of the current Canadian tax system. The package of suggested reforms put forward in this paper contains four principal elements.

Most importantly, we believe that all tax policy changes should be made against the backdrop of a clear, coherent policy framework that sets forth key assumptions and objectives to guide individual policy choices and decisions.

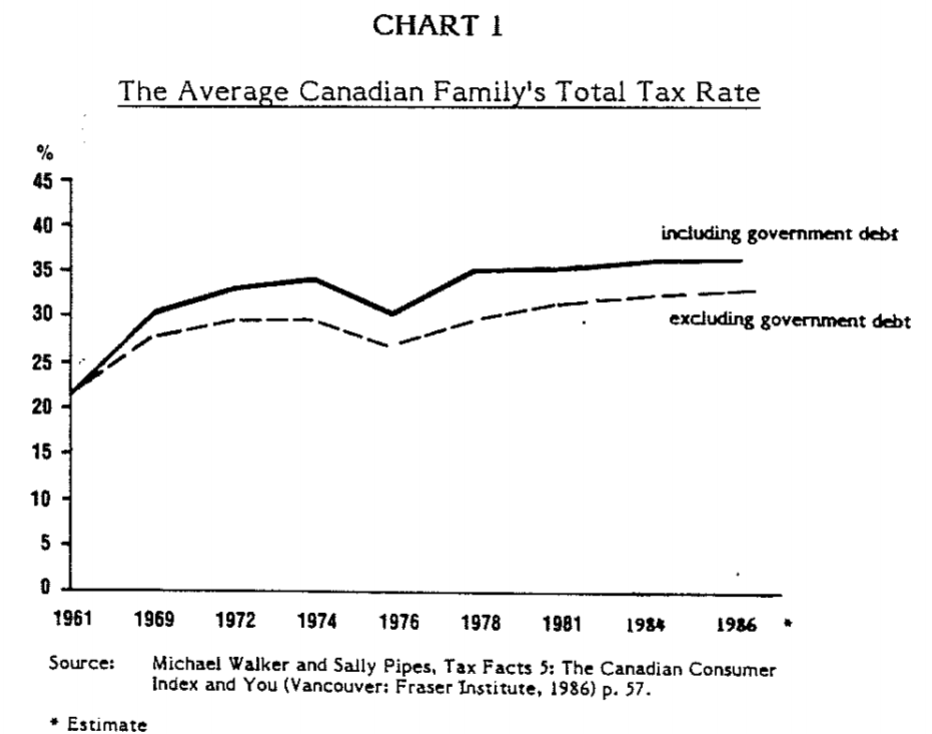

Over the past two decades, Canadians have witnessed a substantial increase in their total tax burden. From 1961 to 1986 the average family's combined total federal and provincial tax rate increased from 22% to over 32% as shown in Chart 1. During the same period, the proportion of Gross National Product (GNP) accounted for by the government sector rose from less than 31% to nearly 48%. The increasing difference between what government spent and what it collected in taxes was accounted for in part by increases in direct charges for goods and services provided by government, but mainly by rising deficits. Since deficits can be regarded as a form of deferred taxation, they should be included in any measure of the long-term tax burden borne by Canadians. Making this adjustment, the average Canadian family's total tax rate grew by more than one-and-a-half times from 1961 to 1986 from 22% to nearly 36% as indicated in Chart 1. Even this figure underestimates the real burden imposed by governments on individuals, since it does not reflect fully the economic costs of the misallocation of resources and effort inherent in our present tax and regulatory structures.

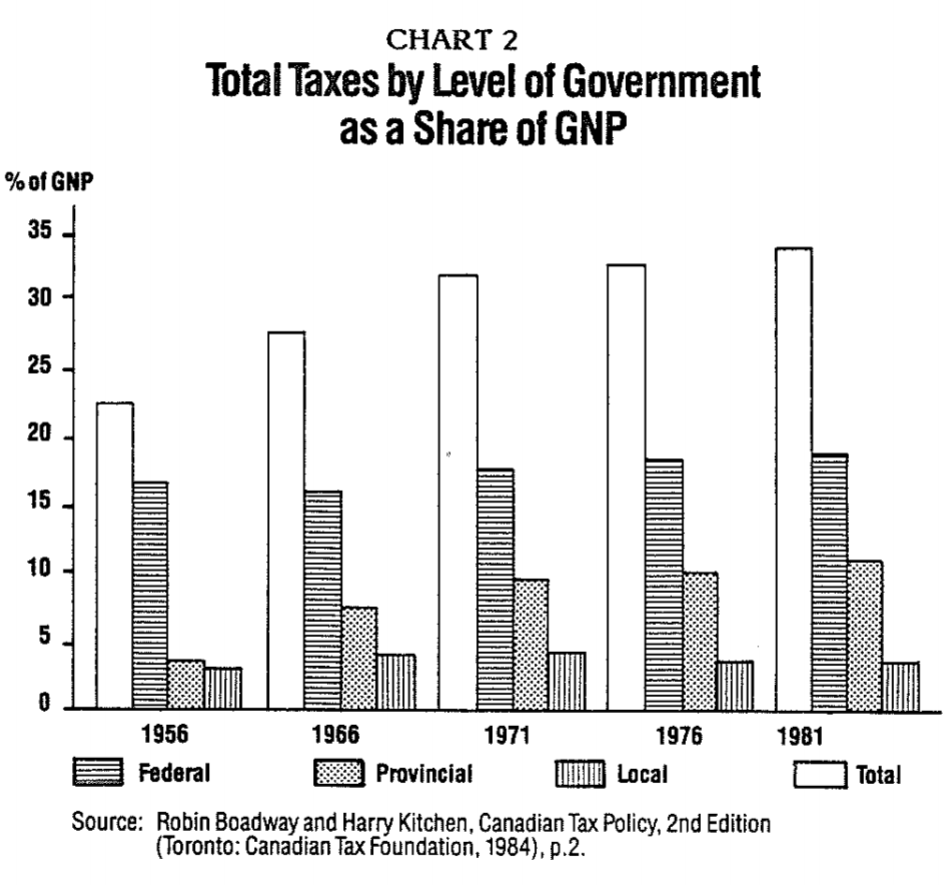

Chart 2 summarizes the growth of taxes in Canada between 1956 and 1981. By the early 1980s, taxes accounted for one-third of GNP, with government deficits amounting to approximately another 10% by the time the 1981-82 recession took hold. The federal government's tax revenues as a portion of GNP have risen modestly since the 1950s, while local government revenues have remained basically flat. The sharpest increase has been in provincial government taxes, which more than tripled as a share of GNP. This development was associated with expanding government provision of education and health services, both of which lie mainly within provincial jurisdiction (although the national government is also involved in funding programs in these areas) and with changes in tax rental and sharing agreements. These changes led participating provinces to impose their own taxes directly instead of receiving a portion of federal taxes, as under the previous rental arrangements. However, in most cases the federal government continued to administer the collection.

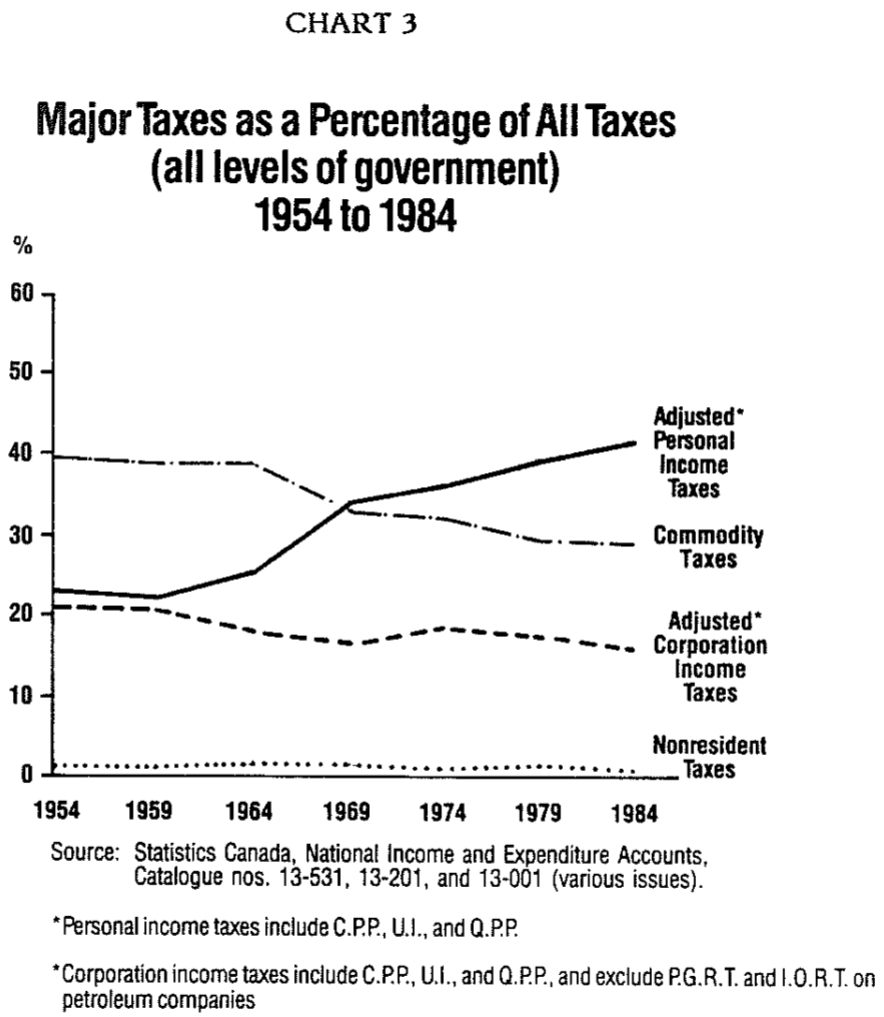

Chart 3 shows the extent to which all governments have relied on just a few taxes for a large proportion of their tax revenues. Note, in particular, the increasing contribution from personal income tax which has become the biggest single revenue source. Although corporate income tax has contributed a smaller percentage of all taxes over this period, it would be incorrect to assume that corporations are not carrying a substantial burden of taxation.

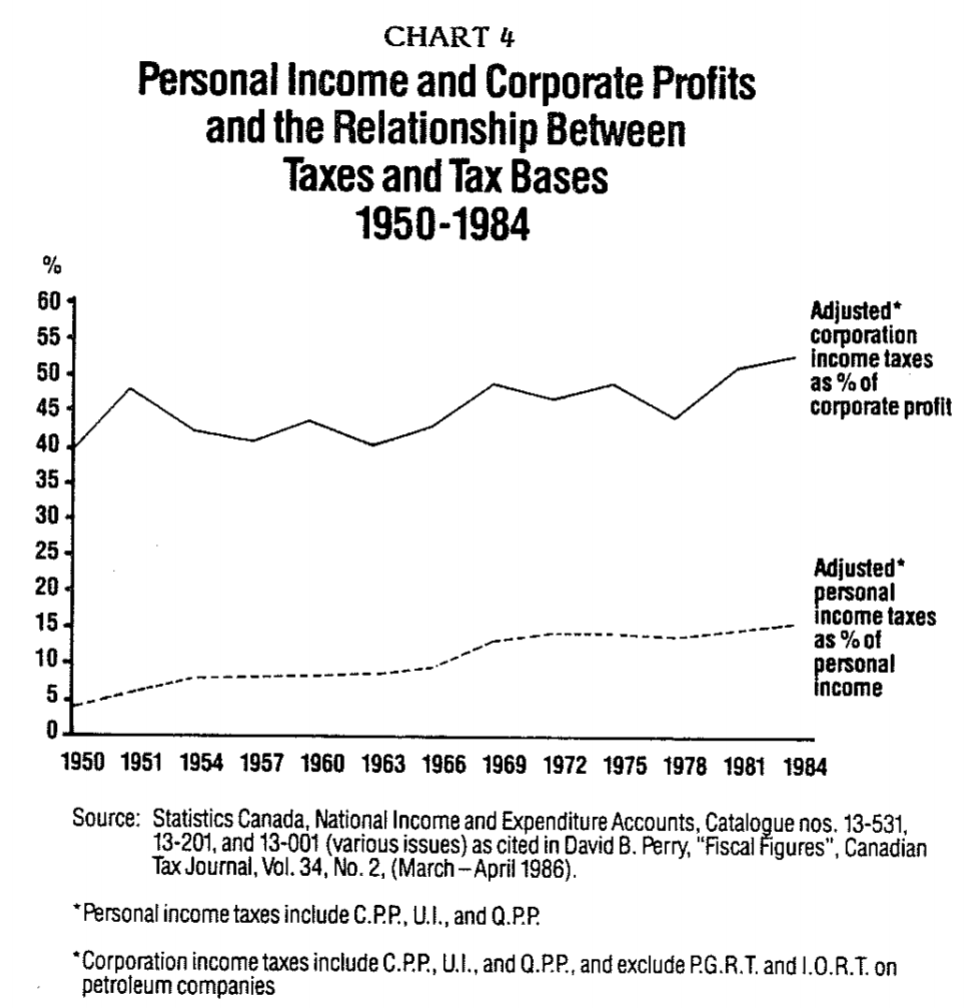

As indicated in Chart 4, in 1984 corporations paid 53% of their profits in income taxes -- adjusted to include unemployment insurance levels (U.I.) and Canada and Québec Pension Plan Contributions (C.P.P. and Q.P.P.) -- while individuals paid 15% of their income in personal incomes taxes -- similarly adjusted to include U.I., C.P.P., and Q.P.P. payments. Corporations tended to pay a gradually increasing percentage of tax from 1950 to 1984, riding from 40% to 53%. During the same period, personal income taxes remained at a significantly lower level but rose even faster as a proportion of income, from 5% to 15%. There are two principal reasons for the apparent contradiction between corporations paying ever larger shares of their income in tax (more than four times the share paid by individuals) yet accounting for a decreasing percentage of all taxes, and conversely, for personal income taxes accounting for dramatically larger proportions of total tax.

The first explanation is that while personal income increased rapidly as a proportion of GNP, from 77% in 1950 to 86% in 1984, corporate income fell from 14% of GNP to somewhat over 9%, with a low of just under 6% in 1982. The second reason is that personal taxes are derived from a progressive rate schedule, thus the rising personal incomes yielded disproportionately higher increases in tax revenues. On the other hand, corporate income is taxed at a flat rate and produced tax revenues proportionate to corporate income.

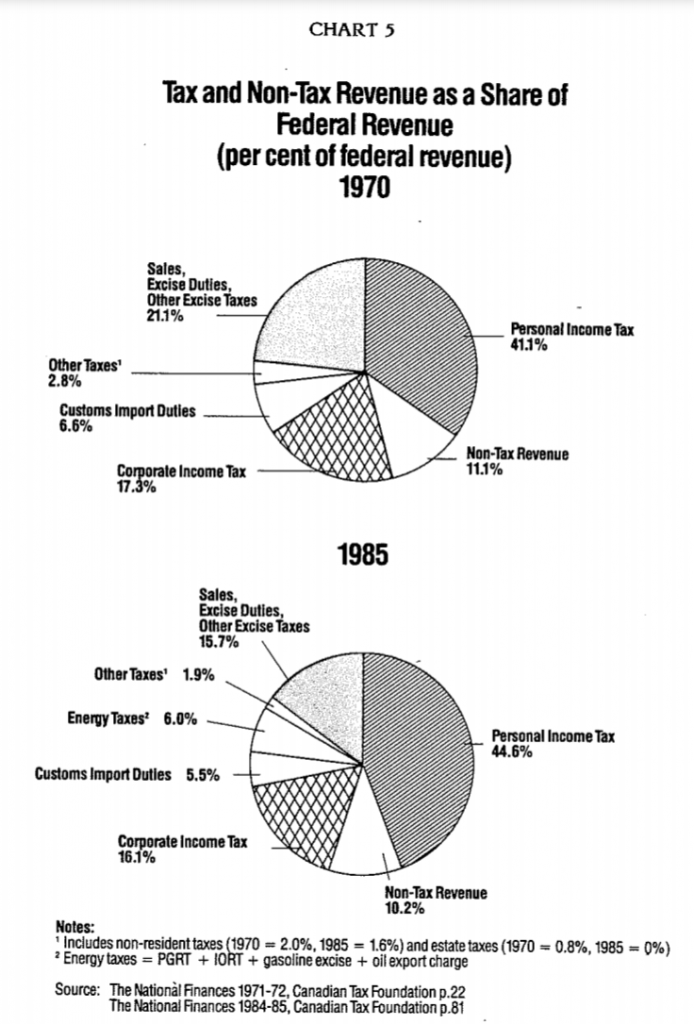

Taking the federal government alone, personal and corporate income taxes combined have provided well over half of total revenues. Chart 5 compares the sources of federal revenue in 1970 and 1985. Once again, the biggest increase has been in personal income tax.

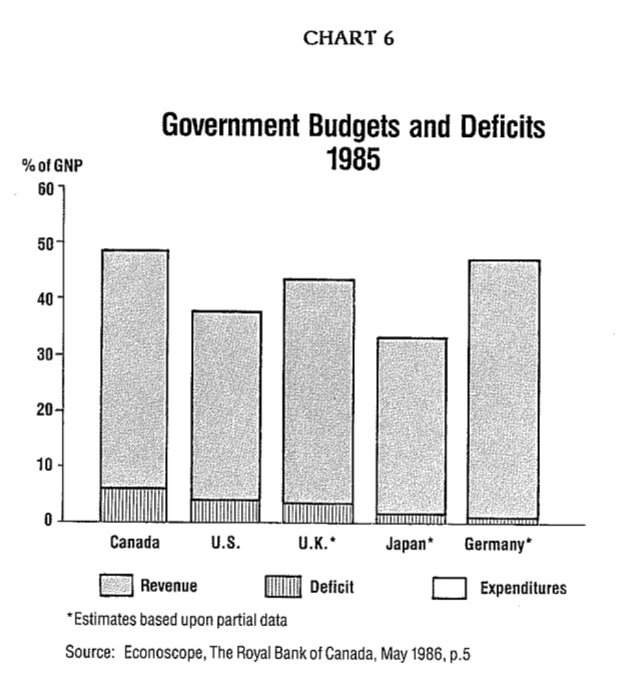

It is also interesting to consider briefly the relative burden of taxation in Canada and other developed industrial countries. Comparing the total tax burden, Canada ranks near the middle among the countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In the early 1980s taxes (inclusive of social security charges) accounted for about 35% of Canada's gross domestic product. In several Western European countries the comparable figure is considerably higher, which indicates that Canadians are by no means the most heavily taxed people in the industrialized world. However, it is worrisome to note that Canada's two largest trading partners impose smaller total tax burdens on their economies than does Canada: in the same period taxes accounted for 30.5% of gross domestic produce in the United States and 27.2% in Japan. This is illustrated in Chart 6, which also shows that Canada has a higher level of government deficit to GNP than any of our major trading partners. While such an aggregate measure of taxation does not in itself provide an adequate basis for determining a country's international economic competitiveness, it does provide a rough indication of the burden being imposed on the economy through public sector taxation. It should also be recognized that Canada raises a larger portion of its tax revenues through direct taxes on income and less through direct transaction taxes on consumption than do many western European countries. As discussed later, this situation has implications for the international competitiveness of Canadian industry.

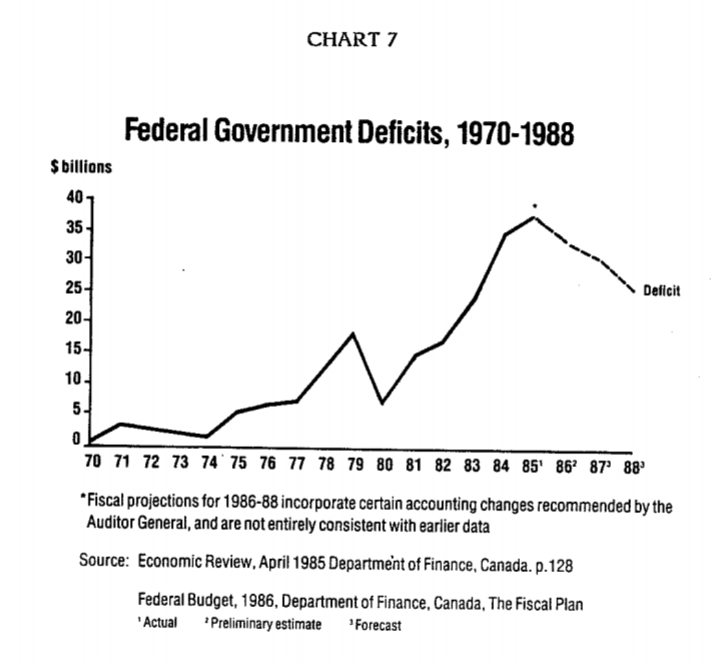

High taxes and large government deficits raise issues concerning the size and role of government in society. They also indicate that our tax structure has failed in its primary purpose of raising sufficient revenue to finance the operations of government. Chart 7 clearly shows the acceleration of this failure in the first half of the 1980s. The projected improvement for the latter half remains to be achieved. The present substantial deficits of governments, together with the growing complexity of the tax system, mean that the true cost burden of government has become hidden and its distribution arbitrary and unclear. There is a saying that "an old tax is a good tax," the thought being that old taxes have worked their way into the structure of the economy and those affected have made the appropriate adjustments in their behaviour and expectations. But some of Canada's old old taxes are not good taxes. Indeed, there is growing evidence that many of our existing taxes take more -- directly and indirectly -- out of the pockets of taxpayers than they add to the coffers of government, in large part because they impair economic efficiency.

For example, studies of the income tax system in the United States conducted by Edgar Browning and John Shoven have concluded that during the 1970s, the marginal cost to the economy of collecting one extra dollar via the U.S. progressive income tax system was between $1.50 and $1.70. A more recent study reported that to provide a grant to the less well-off two-fifths of the population would involve a loss to the economy of $3.50, considering both direct and indirect costs. Another example is Canada's ever-rising federal manufacturers' sales tax, which has harmed the competitive position of Canada industry and, as a result, reduced employment opportunities for many Canadians.

It is impossible to know exactly all the consequences of high levels of taxation. However, it is clear that rising income taxes pose serious risks for a medium-sized, open economy such as Canada's, particularly since tax rates are already high in relation to some of our competitors and our economy is facing unprecedented competitive challenges.

It is a fundamental aspect of the Canadian tax structure that it is made up of taxes that are the responsibility of not only the federal government, but of the provinces and municipalities also. Indeed, the provinces and municipalities in the aggregate account for approximately one-half of the total tax revenue collected in Canada, and are responsible for spending more than one-half of all government expenditures. Canada, far more than our major trading partners such as the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan, has a shared, decentralized tax system.

It follows that the provinces and the municipalities have important roles to play in the reform and restructuring of the overall tax system. The provinces largely rely upon the federal government to define the appropriate base for the personal and corporate tax systems, and therefore have a legitimate and immediate interest in any changes that would have an impact on that base. More fundamentally, the provinces, and through them the municipalities, also need to be actively consulted with respect to other important changes in the system, changes which could have both direct and indirect effects on the positions of these other levels of government. We believe that this dialogue can be pursued most usefully in the context of an overall policy framework.

The provinces, along with the federal government, must recognize their particular responsibilities to help Canada achieve a more rational and competitive tax system. For example, the provinces must not regard the expanded income base suggested for both individuals and corporations as a means of increasing their aggregate tax revenues. Instead, they should agree to reduce their tax rates, in parallel with the reduction in federal tax rates, as long as the integrity of their revenue base is maintained -- perhaps through mutually agreed-upon federal guarantees. In addition, the provincial and municipal governments should demonstrate their leadership by examining their antiquated systems of real estate assessment and taxation, and their hidden taxes on business inputs that raise the costs, and reduce the competitiveness, of Canadian industry. On the other hand, the federal government must demonstrate leadership with respect to reforming at least personal and corporate income taxes, as well as transaction taxes.

It is vital to recognize that the problem in our present tax system are not merely matters affecting business and those individuals who are well off. These problems have an impact on all Canadians, both directly through the unfairness and perverseness of our present tax structure and, more importantly, indirectly through its reduction in economic growth, job creation, and personal opportunities. The situation requires a new and comprehensive reappraisal of our entire tax structure. The Business Council therefore supports the decision of the Minister of Finance to undertake a review of the entire federal tax structure. We call upon the provinces and other levels of government in Canada to become involved in this process to enable a thorough review to be undertaken of the entire tax structure. We recognize that it is neither possible nor desirable to achieve a total overhaul of our tax system in a short period of time, but we do believe that a comprehensive review, rather than a continuation of ad hoc and piecemeal adjustments, is required so that future change in our tax system, accompanied by appropriate transitional measures can be put in place as part of the rationalization of the entire system. Such a comprehensive review is also the only means of reconciling the divergent interests of different groups. It is necessary to demonstrate to those who would lose as a result of particular changes that, through the total package of reforms, they would gain more than they lost.

"To tax and to please, no more than to love and be wise, is not given to man."

Edmund Burke

Tax systems, and even more so, tax changes, are complex. This is a result of trying to achieve specific results by applying imprecise tools in a dynamic and only partially understood environment. Not surprisingly, frequently there are unexpected results, while simple ideas often become bogged down in quagmires of complicated results.

Some of the difficulties inherent in the process inherent in the process could be alleviated by adopting a long-term perspective on the tax system. This chapter outlines the fundamental principles and key design features which the Business Council believes should provide the central policy framework against which proposed improvements to Canada's system of taxation should be measured. In the following chapters these principles, design features, and their implications will be described more fully, together with a more detailed discussion of the rationale for their recommendation and the general policy proposals which flow from them.

Four fundamental principles should form the foundation for taxation in Canada.

1. The primary purpose of the tax system should be to raise the revenues necessary to finance the provision of public services for the people of Canada.

In contrast to this principle, Canada's current tax system is being asked to perform many tasks simultaneously. Besides raising revenue, it is expected to promote economic growth, stimulate employment, foster sectoral development, encourage specific types of investment and activity, reduce regional economic disparities and redistribute income from high-to-low-income individuals. The inevitable result is that it performs none of these tasks well.

The solution is to refocus the tax system on its original purpose: the raising of revenue necessary to finance the provision of public services for the people of Canada. Accordingly, other government objectives should be pursued primarily through direct expenditures. However, programs that are broad in application, that dispense small benefits to each recipient, and for which objective criteria (such as income) determine the selection., can be efficiently delivered through the tax system (for example Child Tax Credits). Were the tax system restructured to conform to the above direct expenditure principle, it could be greatly simplified. In addition, through the more visible, direct financing and delivery of government services and programs, the public would have a much better appreciation of the costs and value of the services they were receiving, and political accountability would be enhanced.

2. The tax system must avoid distorting the normal functioning of market forces in determining rewards for entrepreneurship and work, and in allocating resources within the economy.

There is increasing concern about the inefficiency of using the tax systems to direct and stimulate economic activity. Selective use of taxation in place of market forces has created inefficiencies, resulted in less dynamic economies, and led to a lower standard of living for many Canadians than would be possible with an efficient tax system.

Among the distortions induced by the present Canadian tax system are: a bias against risk investment, resource misallocations due to the incomplete recognition of inflation, the encouragement of debt financing over equity, the biasing of investment toward particular industries, the favouring of foreign competitors through discrimination in the commodity tax system, and a bias against high cost resource production by taxing production rather than profits.

"In its broadest form, then, the tax system has a powerful influence on the allocation of resources in our society, and on the extent to which these resources are produced and consumed. This Commission considers it important that the disincentives inherent in the tax systems be replaced with measures that will encourage the efficient allocation of productive resources and the adoption new processes, products and services. In our view, such measures are necessary components of any industrial policy that will enable Canada to meet its strategic objectives. Tax measures, however, are extremely complex and sensitive, demanding a great deal of analysis and consultation before policy changes are formally presented in Parliament."

Report, Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada , (Macdonald Commission), Ottawa: Supply and Services, 1985, Volume 2, page 209.

These and other detrimental results have contributed to the less-than-optimum performance of the Canadian economy thereby diminishing the opportunities for all Canadians. A more neutral tax system, one allowing greater scope for the exercise of individual effort and market forces, would be more effective in promoting growth and job creation and the development of both large and small businesses.

3. The Canadian tax system must strive to be internationally compatible and competitive in order to promote greater economic efficiency, competitiveness and growth.

Canadian society is characterized by a higher level of government expenditure -- as a percent of GNP -- than, for example, is the United States. This means that Canadians must also accept a generally higher level of taxation. However, it is essential that this be imposed in such a way as to result in the least possible disadvantage to our economy. Under our present tax system this is not the case. An increasingly competitive world economic environment, and the absolute necessity for Canadian producers and entrepreneurship to participate aggressively in world markets, demands that this be corrected. In the interests of all Canadians, the corporate tax system must be internationally compatible and competitive, so as to provide employment opportunities to our growing workforce. Equally, the personal tax system must be adjusted to allow Canada to attract and retain highly skilled and mobile individuals.

These imperatives take on an added urgency in view of the tax reforms now being proposed and implemented abroad. In particular, in the United States pending changes could strengthen the competitiveness of that country, and offer inducements to the most highly skilled members of our labout force to relocate there. Given this environment, Canada cannot afford to retain an outmoded tax system, characterized by high tax rates, a myriad of special exemptions, deductions, concessions, incentives and credits, as well as hidden taxes on business costs which impair competitiveness and impose unnecessary burdens on individuals and businesses.

4. The tax system must be fair and socially responsive, and promote an environment in which individual Canadians can enjoy the maximum opportunity and incentive to develop and prosper.

"Fairness" is in large part a subjective concept, but in a discussion of taxation it has particular characteristics which are commonly accepted. The Business Council believes that it is fair for individuals in similar circumstances to pay similar amounts of tax (horizontal equity). We also believe that it is fair for individuals who earn more to pay more tax -- not just in absolute terms but in relative terms as well, i.e. a greater percentage of income (vertical equity). However, apart from these more common characteristics of "fairness," there is also the concern that every Canadian has the right to have the opportunity to make the most of his or her own life. In this sense, a tax system which retards the growth and development of the economy must be seen to be unfair in the fundamental sense that it denies opportunity. The Canadian tax system can and should be reformed so that it both conforms to our standards of fairness and at the same time expands opportunity.

"The tax system is one of the most important determinants of economic growth over the longer term. When the Royal Commission on Taxation (the Carter Commission) reported in 1966, one of the foremost goals of policy analysts was the establishment of a tax system that was equitable in its treatment of different groups. While equity remains an important goal, tax specialists now stress the need for a system that is calculated to encourage economic efficiency."

Report, Royal Commission on Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada , (Macdonald Commission), Ottawa: Supply and Services, 1985, Volume 2, Page 206.

Consistent with these principles, the Business Council believes that a reformed tax system should incorporate a number of important design features.

In reality, the burden of any tax ultimately falls on the individual, not on organizations, corporations or things. Corporations and organizations pass on tax burdens to individuals in various ways: to consumers of products or services through higher prices, to the suppliers of labour through lower wages and salaries, or to the suppliers of capital through lower rates of return. Taxing businesses or corporations as if they were isolated entities, disassociated from the economy and the general public, only disguises who bears the ultimate tax burden and tends to reduce political accountability.

"All taxes are ultimately borne by people through the reduction in the command over goods and services for personal use. Taxes can, of course, be collected not only from people but also from corporations, trusts, and cooperatives. But organizations such as these cannot bear taxes. It is the people who work for, sell to, buy from, or are members, beneficiaries, or owners of these legal entities who are made better off or worse off by taxes."

The issue arises when shareholders receive income in the form of dividents from corpoarations. In a non-distrorting, efficient tax system, the same total amount of tax should be collected on profits regardless of whether the individual earned the income directly, or whether a corporation was interposed between the business activity and the receipt of income in the form of dividends.

This is not to say that corporate income should be untaxed until distributed to shareholders. A corporate tax ensures that foreign owners of corporations located in Canada pay their fair share before withdrawing profits. It is also effective in preventing the tax avoidance that occurs when there is an unnecessary buildup of non-reinvested retained earnings within a firm. However, these considerations must not be allowed to hide the fact that the corporate tax is another mechanism for taxing individuals. As such, any corporate tax burden borne by the individual must be equitably acknowledged within the overall taxation framework.

Much can be done to simplify the existing tax regime by basing it on sound principles rather than perceived expediency. This is essential if the system is to fulfill efficiently and fairly its prime function: raising the revenues necessary to finance the provision of public services to the people of Canada.

The previous chapter establishes a general policy framework that can be used to evaluate current tax policies and suggest changes in three main areas of taxation – personal income tax, corporate taxation, and transaction taxes. The first two of these are treated in this chapter while a discussion of the quite separate issues relating to transaction taxes is deferred until the next chapter. The background documents and studies on tax policy released by the federal government over the past 18 months have largely focused on corporate taxation. Most of the actual changes made to tax policy have also been in this area. The issues and proposals explored in the next two chapters go considerably beyond the corporate sector. We believe it is desirable to bring forward for discussion wide-ranging reform proposals affecting all types of taxation based on a coherent policy framework as developed in the first chapter of this paper. Based on ample previous experience, we have concluded that incremental, ad hoc changes made without reference to any overall policy framework do not serve the public interest well.

The policy framework outlined earlier suggests that a number of important modifications should be made to the tax system to further the goals of economic efficiency, competitiveness, fairness and simplicity. In broad terms, our proposals would, if acted upon, shift the focus of taxation in Canada away from income – normally reflecting one’s economic contribution to the economy – towards expenditure – reflecting what one removes. The approach taken in this paper would also result in a broadening of the personal and corporate tax bases, both of which have been steadily eroded in recent years through the proliferation of special incentives, deductions, and exemptions that collectively fall under the general heading of “tax expenditures.” 15 Because they narrow the tax base, tax expenditures necessitate higher tax rates to raise the same amount of revenue. Further, and as recently noted by the House Standing Committee on Finance and Economic Affairs, the increasing use of tax expenditures has greatly complicated the tax system and led to growing distortions and inefficiencies in economic behaviour on the part of tax payers. 16 The tax reform strategy advocated in this paper thus consists of four principal components:

The remainder of the present chapter is principally concerned with the issues raised under the first three headings, namely the tax rate, the tax base and integration.

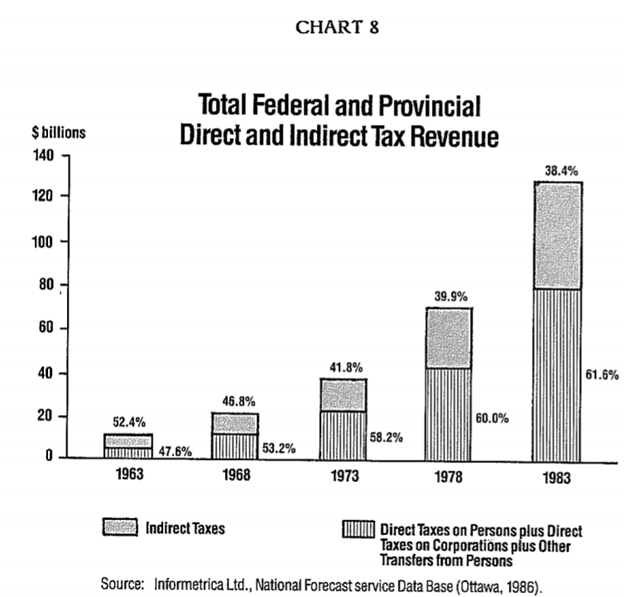

As shown in Chart 8, during approximately the past two decades the federal and provincial governments together have come to rely more heavily on direct taxes which are essentially taxes levied on income . In recent years this trend has been holding steady with 60.5% of total federal and provincial tax revenue deriving from direct taxation in 1985.

Income taxes comprise the central element of the tax system, and therefore should be the main focus of efforts to achieve significant tax reform. There is growing concern in Canada and in several other advanced industrial countries regarding the structure and impact of existing personal and corporate income tax systems. Several key questions are:

The first two of these questions are treated here in some detail; the other three, being more technical, are discussed only briefly.

A. The Personal Tax Base

The tax base issues centres on the choice between taxing “income” or “expenditures”. Should personal tax be imposed at the time revenue is earned or at the time it is spent? The current tax system contains features of both approaches, although it is primarily an income-based system. Proponents of the income base argue that income is a measure of “ability to pay” and is therefore the most equitable alternative. Supporters of the expenditure base argue that expenditure frequently reflects that which one removes from society, and an expenditure base would encourage saving, investment, and the expansion of economic development and national wealth.

“There appears to be merit to building on recent changes that moved personal income tax in the direction of a personal consumption tax…”

Theoretically, it would be possible to shift the personal tax system totally from an “income” to an “expenditure” base. The Macdonald Royal Commission recommended consideration of such an approach, and, as a partial step in this direction, the Business Council favours the introduction of a comprehensive transaction tax (as discussed in the next chapter) which would shift the tax burden towards expenditure. If the direct (income) tax base was itself converted suddenly to an expenditure base, significant disruptions would be inevitable. Moreover, to adopt a pure expenditure base would require not only that all amounts saved be deductible, but that all amounts borrowed be added to taxable revenue. This could create serious problems for individuals making major purchases, such as housing and durable goods. Suddenly changing to an expenditure base would also dramatically alter the distribution of tax burdens across generations of Canadians due to the different saving and consumption patterns characteristics of the various generational groupings.

In light of these considerations, we believe that the base of the direct tax system should continue to be “income”. However, we also believe that contribution limits on amounts saved in deferred savings plans, similar in concept to RRSPs, should be increased. This would help shift the tax structure more towards a consumption base. Provisions should also be made for carrying forward unused deductions to such plans along the lines recently proposed by the government. 21 In addition, there should be greater flexibility with regard to the types of investment options open to such plan holders.

Tax Expenditures and The Integrity of the Tax Base

One of the major problems with the current personal income tax system is the presence of numerous special deductions, exemptions, concessions and incentives. They erode the tax base, necessitate higher marginal tax rates, distort the “neutrality” of the tax system by causing investors to allocate their savings in ways which do not reflect market realities, and prompt question about the overall fairness of the tax system. Concern about the effects of tax avoidance mechanisms on the perceived fairness of the tax system was a key factor behind the government’s decision to introduce the “alternative minimum tax” in the February 1986 Budget.

Many tax expenditures were created to pursue policy objectives which are now of questionable validity, or ones which could better be achieved outside the tax system through the use of direct expenditure programs. The entire panoply of tax exemptions, deductions, concessions, incentives, credits, and tax shelters generally 22 should be thoroughly reviewed to determine: first, whether they are producing benefits to taxpayers sufficient to justify their costs in terms of lost tax revenue; and second, if the benefits outweigh the costs, whether the current delivery mechanism is the most appropriate. If a tax measure cannot be justified under these criteria, it should be eliminated or phased out.

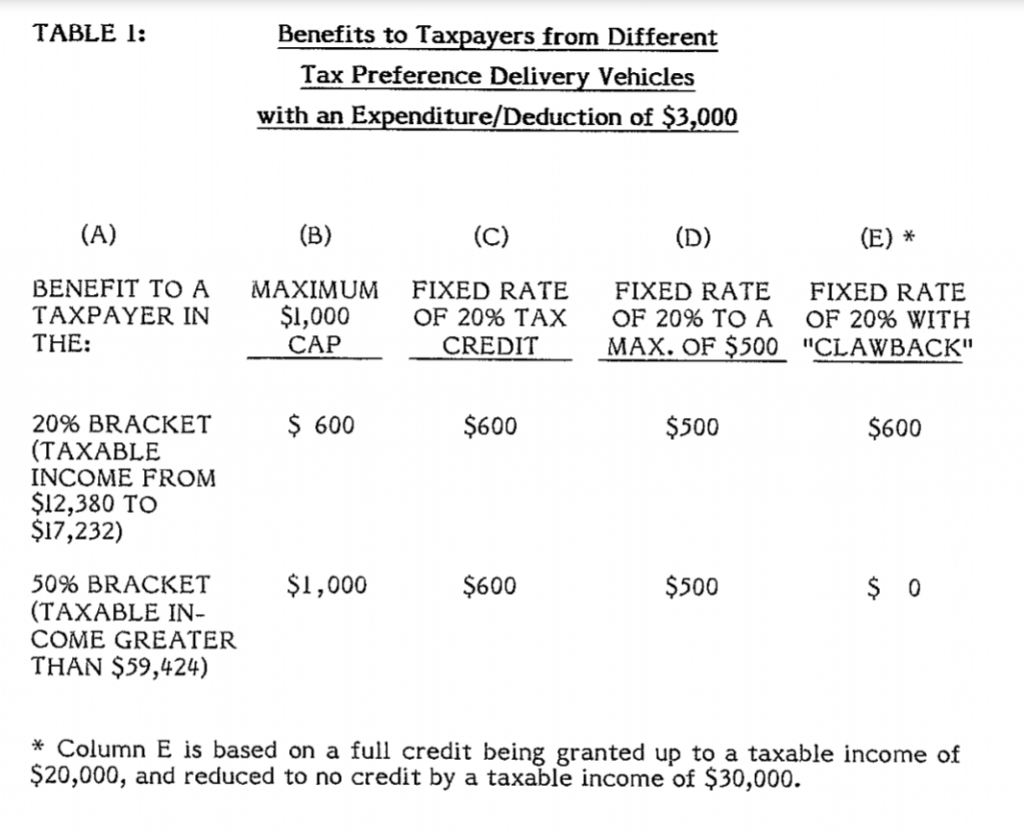

The manner in which many tax deductions, exemptions or expenditures are delivered is a cause for concern. Currently, most take the form of deductions or exemptions. Due to the effects of rising marginal tax rates, greater dollar benefits go to higher-income taxpayers than to those with lower incomes. This raises questions of both equity and efficiency in the distribution of such tax expenditures. There are various ways to address this problem. First, the dollar value of an exemption or deduction could be capped, as is the case with the current $500 “employment expense deduction” and the $1,000 “investment income exemption”. Second, an exemption or deduction could be converted to a “fixed rate” tax credit where the benefit is the same percentage of the expenditure for all taxpayers. Third, a combination of the first and second options could be adopted imposing a fixed percentage tax credit subject to a maximum dollar amount. For example, a 20% credit could be given up to a maximum amount of $500. Finally, an exemption or deduction could be converted to a fixed percentage tax credit subject to a “clawback” with the value of the tax credit reducing as income rises (as is the case with the current Child Tax Credit).

As one moves from a straight deduction/exemption to a tax credit with a “clawback”, the effective progressivity of the tax system is increased and the effective “cost” of such programs reduced. Thus, in this way, changes in the method benefits are conferred through the tax system could be used as a mechanism to maintain a desired level of effective progressivity, while, at the same time, facilitating a reduction in marginal tax rate.

How these alternative mechanisms for delivering “benefits” through the tax system apply to various income levels is illustrated in Table 1 on page 39. It is assumed that taxpayers have some expenditure or deduction which is recognized or encouraged through the tax system. For purposes of illustration, the amount of the expenditure or deduction is taken to be $3,000 per taxpayer. The “clawback” example (column E) assumes that the full credit is received up to a taxable income of $20,000, and is then reduced to zero by a taxable income of $30,000.

We believe that, as a general principle, it would be preferable if the delivery of government programs was divorced from the tax system in favour of selective direct expenditures designed to ensure that benefits went only to those in need. To the extent that the tax system continues to be used as a delivery mechanism, the impact should be made neutral in that it should not selectively influence economic decisions or behaviour. We recognize, however, that in some instances tax credits can be an effective and equitable way to provide benefits to well-defined groups. The current federal Child Tax Credit is a noteworthy example.

Treatment of Capital Gains

The treatment of capital gains should be addressed in any discussion of the personal tax base. The Business Council supports the important objectives which the federal government is attempting to achieve with the $500,000 lifetime capital gains exemption. We too believe it is important to provide a clear signal that government policy favours personal investment, entrepreneurship, and risk-taking. However, we suggest that in the longer term these objectives could be attained with greater efficiency and fairness through the more fundamental reforms we are urging in this paper, reforms which would provide a fairer and more efficient treatment of all savings and investment. Should the broad changes we are proposing be implemented, and subject to a provision allowing for inflation adjustment to the cost base of assets, serious consideration could then be given to the phasing-out of the existing capital gains exemption and to the inclusion of capital gains in the tax base as normal income.

B. The Corporate Tax Base

As with personal taxation, present corporate taxation resets upon an income base with numerous modifications. Over the years a number of alternative bases have been proposed including “business expenditures” and, more recently, “cash flow”. Under a business expenditures base the net business costs incurred by a company would be taxed instead of its profits. A cash flow base, which is often associated with an expenditure base at the personal level 23 , would result in taxing corporations on the basis of their net cash flow – i.e. the difference between total revenues and total costs including the full net cash cost of capital expenditures. 24

Proponents of a net business cost base argue that such a tax rate would stimulate efficiency and cost consciousness and eliminate the distortions caused by taxing profits at the corporate level. Alternately, those who support a cash flow base assert that it would promote investment and economic growth since all capital expenditures could be written off for tax purposes in the year which an investment was made, thus avoiding any penalty on the acquisition of capital assets. However, moving to either base for corporate taxation could bring a number of disadvantages. For example, no other country employs such systems. If Canada were to adopt either approach, it would create difficulties in our relationships with international trading partners and with the availability of foreign tax credits to investors abroad. Further, under either approach, tax revenues to governments would tend to be highly variable. With a cash flow base, interest expense would not be deductible, putting firms currently in a high debt position in great difficulty. For these and other reasons we believe that corporate taxes should continue to be assessed on the basis of income, but that the present system should be restructured.

The Integrity of the Base

Reform of the corporate tax system should have as its principal objective improving the efficiency of Canadian business so as to provide benefits to all Canadians. We believe the way to achieve this goal is through a more neutral tax system that encourages business to rely on market forces, not government incentives. Neutrality in this context refers to equal tax treatment for all types of investment: in principle, one form of investment should not be given preference over another. As with the proposed changes to the personal tax system, we believe that many existing exemptions, deductions, concessions, incentives and credits in the corporate tax system should be removed or cut back, and greater equality should be achieved in the application of others. The objective would be to equalize effective tax rates for different investments and activities in order to improve resource allocation and economic efficiency. This goal of neutrality would contribute towards the essential condition that Canada’s industries operate within a tax environment which allows them to be competitive with our major trading partners. The federal government has already begun to move towards what is regarded as a more neutral system through its elimination of the investment tax credit and inventory allowance, while also slightly lowering corporate income tax rates. Unfortunately, these changes have not been made in the context of a broad reform of our system that would reduce or eliminate other tax policies that hamper business efficiency and competitiveness, and result in differential treatment of investment.

Canada’s resource industries present special problems in the application of a uniform corporate tax structure, primarily due to the existence of substantial provincial royalties and other resource-specific forms of taxation. A concerted and co-operative effort should be made by governments to rationalize the taxation systems applicable to the resource industries in order to include those industries in a stable, integrated corporate tax framework. Such a framework should continue to recognize the special issues related to the high initial costs and risks associated with resource exploration and development, through allowing producers to recover a significant portion of their capital costs before full taxation of resource profits commences. At the same time, the system should seek to reduce the distortions now caused by taxes and royalties levied on gross revenues or on other bases other than net income.

Capital Cost Allowances

The present system of capital cost allowances has served the Canadian economy reasonably well. It has provided some measure of incentive for business investment within the context of an overall tax system that has contained many disincentives for investment, such as sales taxes on business capital spending and the failure to index depreciation deductions for the effects of inflation.

To the extent that these distortions are removed from the tax system and corporate rates are reduced as recommended later in this paper, it may be possible to modify somewhat the system of capital cost allowances to provide maximum permitted deductions which more closely conform to actual rates of capital consumptions. The system must, however, retain a degree of accelerated allowances as an offset to inflation and, to recognize that, with today’s fast-paced technological change, business investments frequently become obsolete long before they are physically worn out. In addition, the system of capital cost allowances should ensure that the same set of rates apply to all industries in order to more equitably encourage investments throughout the private sector.

As well, the capital cost allowance system must be designed so that the overall environment for Canadian industries is competitive with our major trading partners. This will require a comparison of the impact of the foreign and domestic tax systems as well as an appreciation of the generally greater capital intensity and higher cost of capital for industries in Canada. In this regard, it is noted that while the major tax changes in the United States eliminated so-called “business preferences,” they did not result in any sharp cut back of depreciation allowances on most industrial machinery.

Treatment of Losses

In order to reduce the present bias of the tax system against risk-taking, there should be an expansion of corporate “loss flow through” provisions so that losses can be transferred among members of a corporate group. The present lack of such a system means that a corporate group comprising profitable and unprofitable corporations can be forced to pay tax on an aggregate amount which exceeds its combined net taxable incomes. This would not be the case if the corporate group was permitted to offset gains and losses.

At present, mechanisms exist which allow the transfer of losses in certain circumstances between corporations, with such transfers being most practical in situations involving wholly owned subsidiaries. However, the existing situation is equitable because some corporations are prevented from taking advantage of such transfers due to legal impediments – such as those requiring certain types of business to be carried on as separate entities – or practical considerations relating to minority interests. Meanwhile, other corporate groups, without such restrictions, may enter into complex, and sometimes costly, transactions to allow the transfer of losses and deductions between corporation in the group. 25 the interprovincial revenue aspects of the needed changes in this area will require special consideration. Provincial concerns about potential declines in their tax revenues will need to be allayed.

Similarly, small, incorporated businesses should be allowed the option of being treated as partnerships for tax purposes along the lines of sub-chapter S in the United States Internal Revenue Code. This would allow both income and losses of such companies to flow directly through to shareholders. 26 The impact of this proposal on small business is discussed in greater detail later in this paper.

C. Integration of the Personal and Corporate Tax Systems

Under current Canadian tax law, income originating within corporations is in effect taxed twice – first at the level of the enterprise itself, and then when it is realized by shareholders in the form of dividends or capital gains from the sale of stocks. 27 This situation is widely recognized to result in inequitable and anomalous treatment. 28 there are no persuasive reasons why income earned by corporations should be taxed more heavily than income earned by unincorporated business enterprises. Yet the former are subject to “double taxation”, while in the case of the latter, the income is taxed at the personal level only. As part of the tax reform advocated in this paper, the total tax paid on income earned through the operations of a corporation should not exceed that which would have to be paid of the same income were earned directly by an individual.

As noted earlier, there are sound reasons why it is appropriate to continue to tax income in the hands of corporations. These include such considerations as the efficiency of corporate withholding comparing with direct attribution of income to shareholders, ensuring that foreign shareholders pay their fair share of tax, and preventing tax avoidance which can result from the undue buildup of non-reinvested earnings within a firm. However, income that is subject to tax at the corporate level should give rise to a full offsetting credit for the taxes paid on such profits when the income is passed on to shareholders in the form of dividends. This can be achieved only if the personal and corporate tax systems are integrated; it can occur efficiently only if the top rate of personal tax is close to the standard rate of corporate tax.

The Business Council appreciates that serious questions arise with regard to the exact nature and amount of dividend tax credits. Specifically, should these be based on the average tax rate, or should they be restricted to the actual amount of tax paid by a particular corporation? However, these problems would be less significant with the adoption of the proposals concerning the corporate tax base (which would bring the base more into line with accounting income), as well as those concerning lower personal and corporate tax rates as discussed in the following pages.

The cornerstones of sound tax reform are a lowering of both personal and corporate tax rates and an expansion of their tax bases. But in order to preserve neutrality in the taxation of income earned in different ways, and to avoid creating incentives for the shifting of income from one form to another, it is important that the maximum income tax rates under the corporate and personal tax systems be essentially equal, and that in general the corporate and personal tax systems be integrated to the greatest extend possible.

To be equitable, however, personal income taxation should continue to be progressive so that the average rate of taxation should rise with income. The current personal tax system achieves this by applying highly progressive marginal tax rates to a tax base narrowed by numerous exemptions, deductions, incentives, concessions, credits and other tax shelters. We believe that this structure is fundamentally unsound. Highly progressive marginal rates give rise to great pressures for special tax concessions and lead to tax avoidance and evasion. For these reasons, high marginal tax rates inevitably cause complexity and raise questions of fairness; they also reduce incentives to work, save and invest. Overall, such a structure damages the efficiency and competitiveness of the economy. 29

There is some evidence that as the top marginal rate rises above 30%, the incentives to avoid, or even evade, taxes increase rapidly. There is little doubt that top marginal tax rates in excess of 50% create strong incentives to avoid taxes. High marginal tax rates have negative effects on economic growth, and thus on the ultimate size of the tax base. They stimulate the growth of the underground economy. They encourage individuals to spend increasing amounts of time and money in non-productive ways trying to avoid the resulting tax liabilities. 30 and they deprive all Canadians – not just those at the top of the tax brackets – of the benefits which a more vigorous and soundly based economy could provide.

Estimates of the adverse effects of high marginal rates have been made for the United States, Sweden, and elsewhere. Some studies have concluded that the cost of raising one additional dollar of tax revenue through the respective income tax systems was between $1.50 and $3.50 in the United States and between $3 and $7 in Sweden. 31 While those and other estimates must be viewed with caution, the general conclusion is that the use of the tax system to redistribute income is costly to the economy and hence to the ability to support growth in jobs and living standards.

The Effects of Past Rate Reductions

In addition to evidence concerning the overall economic costs associated with high marginal tax rates there is evidence of specific beneficial effects flowing from their reduction. 32 (For details, consult Appendix 4.) In both the United States 33 and Canada 34 , reductions in top marginal rates have resulted in significant increases in income reported and in total tax collected from upper-income individuals. However, reductions in the middle and lower income ranges in the United States and elsewhere have resulted in large losses in revenue. The short-term explanation is to be found in the fact that the reduction in top rates suddenly made a great many tax shelters “unprofitable” and lured back into the tax system a substantial amount of previously untaxed or sheltered income. Over the longer term, additional benefits should result from the positive incentives of lower marginal tax rates for purposes of saving, investment and individual effort. In short, these data suggest that if the objective is to increase the percent of total taxes paid by upper-income individuals, this can be achieved best by lowering top marginal tax rates.

Finally, it is worth noting that high marginal tax rates are not only of concern to Canadian with high incomes but also to those with low incomes. This results from the combined effect of the income tax system withdrawing income through taxation with “tax back” arrangements applying to most social assistance programs whereby payments are reduced as earnings increase. Because of these features, social assistance recipients often face marginal rates of 100% or more on earned income. This removes any Incentive for these individuals to try to improve their situation by moving into the official labour force and also creates incentives for them to sell their services in the underground economy.

Tax Changes in the United States

This is a logical point to note the radical reform of the personal and corporate income tax systems in the United States that are now being introduced. The changes, while complex, will essentially result in substantially lower personal and corporate income tax rates, but with a broadened tax base and a more neutral tax system, one that seeks to provide less government direction of investment. 35

Under these tax changes, the top marginal federal income tax rate in the United States for individuals will be reduced to 28% by 1988 (33% in certain bands of income), representing the lowest personal tax rates in over 50 years. The standard federal corporate tax rate is also to be reduced, to 34%. (Of course, in comparing U.S. tax rates with the combined federal and provincial tax rates in Canada, account must be taken of the net impact of state income taxes, which typically add up to a further 5% of tax to the U.S. federal rates.)

In the future, the fact that the top combined federal and provincial marginal rates in Canada will be substantially higher than corresponding rates in the United States could lead Canada to face an outflow of highly skilled and productive individuals, a loss of capital and enterprise, and a deterioration in the competitiveness of certain industries. 36 Given the close proximity and large importance of the U.S. market to our economy, a major disparity of this sort cannot be allowed to continue.

Proposals for Canada

The Business Council strongly believes that there should be a significant moderation in personal tax rates across the board with a sharp reduction in the maximum rates of tax in both the personal and corporate income tax systems. Such a change would provide for a reduction in income tax burdens, on this account alone, to all individual taxpayers, as well as a corresponding reduction in corporate tax rates. The substantial revenue cost arising from such reductions in rates would be met, in part, by an extension of the corporate and personal tax base as recommended elsewhere in this paper, and in part through a shit of a portion of the total tax burden from direct taxes to indirect (transaction) taxes.

More specifically, we recommend that, ideally, the top personal tax rate should not exceed 35% including both federal and provincial portions of the tax. Some moderation in tax rates below this level should also be introduced. Furthermore, to ensure a proper integration of the personal and corporate tax systems and to provide for simplification in the avoidance of abuse, a single corporate tax rate roughly equivalent to this top personal rate should also be adopted. 37

The single, flat corporate tax rate advocated here implies an increase in the tax currently applicable to a portion (the first $200,000 of taxable income) of incorporated Canadian-controlled small businesses, as this income is now eligible for a special lower rate of corporate tax. However, there are a number of compensating factors which would make the overall system advantageous to small business. First, an election to permit small business corporations to flow deductions and losses through to their shareholders’ incomes would allow the owners of such companies a total integration of their corporate and personal tax structures. Not only would this avoid any possibility of “double taxation” of income from corporate sources flowing through to shareholders of such companies, but the ability to flow through deductions and losses would grant immediate relief to the shareholders for such items, thereby reducing business risks and improving their ability to raise capital. Second, under our proposals, the top personal rate would be reduced from the current 50% to 60% to about 35%. This would reduce the effective tax rate paid by most owner-operators of small businesses. Third, we are proposing a dividend tax credit mechanism which would fully reflect corporate taxes paid, thus eliminating the possibility of double taxation of income for those small, privately held corporations that do not select the flow-through treatment of their income and losses. Under the current tax system, as revised in the February 1986 budget, even relatively modest-sized corporations with fluctuating incomes, as well as larger corporations, can be placed in a position where their shareholders will not receive full credit for all of the corporate tax they are required to pay.

Despite these factors, the Business Council recognizes that the changes proposed could cause a modest increase in the rate of tax on retained earnings in Canadian-controlled private companies. Because such businesses do suffer disadvantages in raising equity capital and because of the traditional support given to this important part of our economy, more favourable treatment should be accorded, during a transition period, to the earnings of such companies retained in the corporation up to a maximum annual amount. By way of comparison, the recent tax changes proposed in the United States provide special treatment for small businesses in the form of reduced tax rates (15% and 25%) up to a taxable income level of $75,000. The benefits of these lower rates are then “clawed back” as income increases to $350,000, such that after this amount a corporation pays 34% on its total income.

Three additional issues deserve consideration in connection with the tax reform strategy outlined in this paper: the impact of inflation on the tax system; the taxation of irregular income flows; and the relationship between the tax and income transfer systems in Canada. Each is briefly discussed below.

Adjusting for Inflation

The impact of inflation on the tax system is widely recognized to be a serious problem, for both business and for individuals. As noted in a recent Brookings Institute study:

“Among the most serious defects of the tax system are those that arise from its interaction with inflation. If a tax system is based on values unadjusted for inflation, it will mismeasure real economic depreciation, inventory costs, capital gains, and interest income and expense. This systematic measurement of taxable income produces inequity… But it also causes inefficiency by distorting economic decisions; and it adds to complexity by promoting transactions either to escape, or to capitalize on, the effects of inflation”

In the case of business, the failure to adjust the tax system to recognize inflation results is an understatement of the deductions for depreciation and inventory, and an overstatement of income for tax purposes. 39 in the case of individuals, the failure of the tax system to take inflation into account has many adverse affects. As a dramatic example, consider that without inflation adjustment, an individual in a 50% tax bracket, facing 10% inflation and 12% interest rates, must put aside $3.40 now to save $1.00 of real, after-tax funds available to him 30 years from now.

Further, inflation causes the well-known problem of “bracket-creep” for individuals whereby inflation-driven increases in a person’s nominal income pushes him or her into a higher tax bracket – or, in the case of some low-income households – may move them from a non-taxpaying to a taxpaying position. 40 The preferred way to deal with this problem is to index tax brackets and exemptions so as to recognize the loss in the purchasing power of money. This policy was introduced in Canada in the mid-1970s, although full indexation was suspended in 1985.

With respect to the taxation of business profits, recognition of the impact of inflation on the determination of taxable income should also be given. However, with relatively low rates of inflation, this probably can be achieved best through appropriate, ad hoc measures rather than through a wholesale and, of necessity, complex effort to index the entire system of determining business income.

The Taxation of Irregular Income Flows

Ideally, the personal tax system should be completely neutral as to the timing of the receipt of income. That is, personal tax liabilities should not vary solely as a result of the timing of revenues earned. If the impact of the direct tax system falls more on expenditure through the use of registered savings plans, then this problem becomes less serious since such savings are non-taxable until they are withdrawn for consumption purposes. 41 But, as long as the system continues to be based on “income”, it should incorporate an efficient, income-averaging method in order to take irregular flows into account.

Improving Tax Compliance

We believe that the measures advocated in this paper would improve tax compliance and the smooth functioning of the revenue system. First of all, the tax system would be, and be perceived to be, fairer to all Canadians with a more rational distribution of burdens. Secondly, the tax system would rest on understandable basic principles, and with a considerable simplification in its application due to such measures as: a simpler rate structure, the elimination of many often complex incentives and special treatments, and the reform of the antiquated system of transaction taxes. Such an improved system should therefore encourage a greater degree of compliance on the part of taxpayers, and should also make easier the job of the revenue authorities in enforcing our statutes fairly, and in reducing the scope of the “underground economy”.

The Tax and Transfer Systems

A final issue concerns the interaction between the tax system and the current system of income transfers to individuals. As noted above, many social assistance recipients face implicit marginal tax rates of 100% on additional income. This problem of perverse disincentives has been examined by the Business Council’s Task Force on Social Policy which will be releasing a major report on social policy reform in the near future. 42 Briefly stated, a system is needed in which social assistance recipients are encouraged to earn additional income and to join the official labour market. This may involve measures to lower the implicit marginal tax rates they face when they start to earn in come through integrating the tapering-off of support programs with tax rates.

As noted previously, in recent decades an increasing proportion of total federal and provincial tax revenue has been raised through direct taxes and a decreasing share through indirect taxes (sales and excise taxes, customs duties, and other transaction taxes). This change has shifted the burden of taxation away from expenditure and towards income, and imposed a gradually widening wedge between the return earned by a firm and that received by investors, thus increasing the real rate of return required to justify investment outlays. Income taxes tend to bias personal financial decisions towards current consumption. Because of this, they discourage investment, saving and entrepreneurship. Over time, such a tendency will diminish the prospects for job creation, productivity gains, and overall competitiveness in the economy. To deal with this problem, a more careful balance must be struck between the taxation of income and the taxation of expenditure (or consumption).

If all Canadians are to enjoy the best possible opportunities in the years ahead, investment must be encouraged and ways found to pay for the country’s large, expensive public sector that are more conducive to economic growth and improved competitiveness than current tax policies. In our view, this can be partially accomplished by restoring a more equal balance between the revenue demands placed on the direct (income) and indirect (expenditure or consumption) tax systems. In the process, it would be desirable to move towards an integrated, simple, and comprehensive tax in each area. For these reasons, as discussed in the previous chapter, as well as a single, comprehensive tax on expenditures or transactions. The latter is the subject of the remainder of this chapter.

The federal government and the provinces employ a mix of complex and overlapping transaction taxes. Some of them are obsolete and their overall impact can be perverse. At the national level, the present federal sales tax is widely recognized as harmful to our economy and to domestic production and employment. It is a tax which discriminates against domestic producers, and in favour of imported goods, in at least two principle ways:

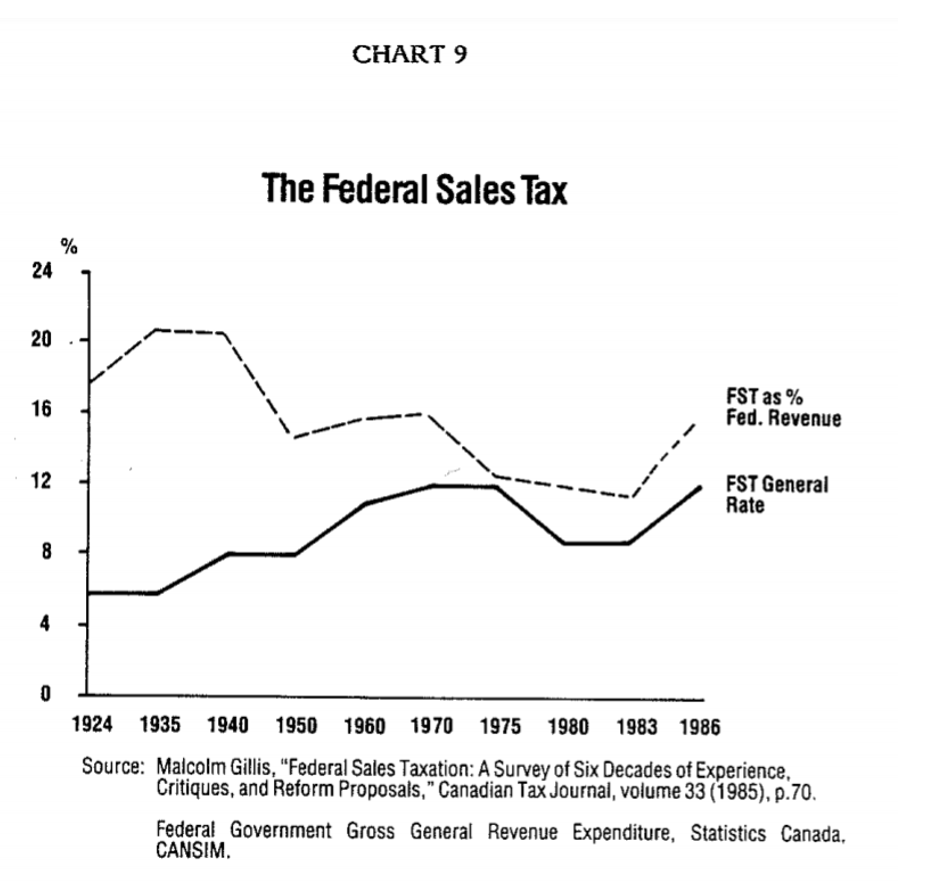

In addition, there is frequent difficulty in determining the value upon which the federal sales tax should be levied. In principle, the tax is based on the price at which a manufacturer would sell goods to a wholesaler. However, with integrated companies the wholesaler is bypassed, and this, together with other transfer pricing activities, has led to the development of often artificial and subjective notional values upon which to base the manufacturers’ sales tax. The overall effect of these anomalies is that the tax distorts both production costs and final demand, with consequent damage to market efficiencies. As noted in a recent article, “Canada is now the last remaining industrial nation using this fiscal relic of the 1920s.” Chart 9 provides some key data on the evolution of the tax.

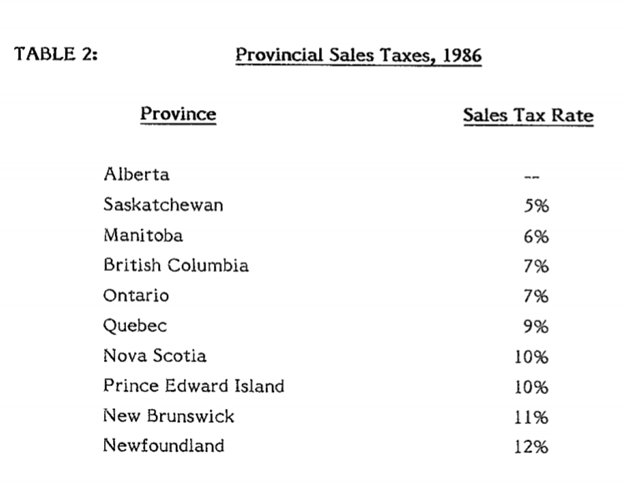

The federal sales tax is also a “hidden tax”: the consumer is not readily aware of its existence when he purchases a product. This is in contrast to the retail sales taxes levied by most provinces. This tax “applies to the selling price of goods sold for final use or consumption unless specifically exempted by law”. Exemptions include a wide variety of items, such as food and prescription drugs; most services are also exempt from the tax. Although it is levied on consumers, the retail sales tax is collected by vendors who forward it to their provincial governments. The rate of sales taxation varies across the country, with Alberta standing alone as the only province never to have instituted such a tax (see Table 2.)

A comprehensive transaction tax, applying through to the retail level, deserves serious considerations as a possible replacement for many current transaction taxes. Such a tax, designed with an effect similar to multi-stage value added tax and applying at each stage of the production-consumption process, could offer significant advantages to domestic producers. It would improve the efficiency of the economy by ensuring that the burden of the tax remained constant percentage of final selling prices, thus spreading the burden of the tax fairly and efficiently among the consumers of taxed commodities and services and preventing economic distortions. It could also assist in restoring a more equal balance between the taxation of income and expenditure, would reduce the complexity of the present transaction tax system, and would ensure that the public was more fully aware of taxes being imposed.

Ideally, this comprehensive tax would be levied co-operatively by the federal and provincial governments with provision for the provinces to set separate rates for their part of the tax on a destination basis. It could replace not only the present federal and provincial sales taxes, but also a multitude of other indirect taxes which contribute to business costs, such as the business property taxes, capital taxes, and perhaps even premiums for workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance, as the present burden of these taxes hampers the ability of Canadian business to remain competitive. We also believe that a new, comprehensive transaction tax should replace revenues that may be required to make up for any overall decrease resulting from implementation of the person and corporate income tax reductions advocated in the previous chapter.

Because the introduction of a broadly based transaction tax could impose an increased tax burden on lower income Canadians, its introduction should be accompanied by a selective mechanism to compensate low-income individuals for any additional tax burden that they would bear. This compensation could be delivered as a fixed rate, income-dependent credit in the personal income tax system (perhaps similar to that introduced in the February 1986 federal budget).

It should be noted, however, that an individual’s total lifetime spending bears a much closer resemblance to his total lifetime income than does his spending in one year to the income of that year. Accordingly, when viewed on a long-term basis, the burden of a broadly based consumption tax is in rough proportion to income. A broadly based consumption tax, in terms of its lifetime incidence, therefore is not markedly regressive. Even in the short term, given the capricious burdens of the present federal manufacturers’ sales tax, an appropriately designed broadly based consumption tax should not be significantly more regressive than the present federal sales tax.

The Business Council is aware that the federal government is currently studying the introduction of a comprehensive business transfer tax. In effect, this tax would probably be a modified, value-added tax levied on the balance of revenues over deductible costs, rather than on the transaction-by-transaction basis followed in the value-added taxes adopted in Europe and elsewhere. While full details concerning the contemplated business transfer tax are not yet available, the adoption of such a tax, adjusted to reduce some of the compliance complexities that have been plagued somewhat similar taxes abroad, would be a positive step in the reform of the Canadian tax system. It is recognized that this tax will be imposed on businesses in respect of their net value added, and there is no assurance that its burden can be passed on to purchasers in all circumstances. However, final comments on a business transfer tax must be reserved until complete information becomes available.

In view of these considerations, we recommend that the transaction tax policies of both federal and provincial governments be restructured co-operatively along the following lines:

The tax policy reforms outlined in the previous chapters reflect the view that the Canadian tax system is deeply flawed and in need of a major overhaul. Developed over many years in an ad hoc and often incoherent manner, the tax system does not achieve many of the key objectives which have been assigned to it. It is retarding to our long-term economic growth and serving to depress investment; it fails to allow the economy to maximize production of goods and services, and jobs for Canadians; and it does not raise the revenues required to pay for our public services. Above all, the present tax system fails to meet the tests of fairness and inefficiency rightly demanded of it by Canadians. For all of these reasons, the Business Council believes that the time for comprehensive tax reform has arrived, and fully supports the recent initiative of the federal government, together with initiatives by other governments, to undertake a fundamental review of our present tax policies.

To sum up our views in this paper, a sound tax system should be unbiased, allowing economic decisions to be made on the basis of market realities rather than tax considerations. Tax reform should aim to achieve substantially reduced marginal tax rates, a broadened tax base and a shift in the incidence of taxation from income to consumption. The Business Council is convinced that changes in these directions will increase economic efficiency, to promote international competitiveness, facilitate investment and reduce the current bias against risk-taking, entrepreneurship, and effort.

Such a reformed system should improve both the actual and perceived fairness of taxation, not only in terms of the distribution of taxes paid, but also in terms of the opportunity which enhanced economic activity and greater freedom for personal decision-making provides for Canadians to make the most of their lives. Apart from these powerful domestic considerations, Canadian tax policy should be sensitive to the need to keep our system of taxation competitive and compatible with those of our major trading partners, especially the United States.

The Business Council is confident that the tax reforms proposed in the preceding chapters would help to achieve these objectives. These changes are consistent with the fundamental principles and designed characteristics outlined at the start of this paper. Because our proposals involve important tax trade-offs and compensating adjustments, they must be viewed as an integrated package. While we realize that any suggestions for change in an area as important as taxation are likely to be subject to intense debate and thus there may be a temptation to adopt only the least controversial elements, we urge that this temptation be resisted. The reform process must be approached from a global perspective and not in a narrow and piecemeal fashion, and with an appreciation that costs or losses to taxpayers in one area are more than offset by benefits in another. Only through taking this broad and long-term view of tax reform can we achieve significant improvements in our tax system and in the well-being of all Canadians.

The Business Council welcomes recent federal government plans for a comprehensive review of the Canadian tax system. Such a searching appraisal is badly needed, and should lead to proposals for reform that command broad support throughout the country. In order to participate constructively in the national debate on tax policy issues, the Business Council decided to establish a Task Force on Taxation Policy in 1985. The Task Force’s mandate was to prepare a taxation policy framework and a set of general policy proposals for Canada. This paper represents the fulfillment of those objectives. The purpose of the policy framework is not to offer detailed recommendations on every aspect of the tax system, but instead to articulate an integrated set of principles and policy directions against which specific reform proposals can be assessed and evaluated.